Eating Disorder Treatment as Assimilation: Parallels with Native Boarding Schools

This blog contains references to Native American boarding schools, including forced removal, cultural erasure, and institutional violence. These topics may be distressing for survivors, descendants, and others impacted by these histories. It also discusses eating disorder treatment and medical harm. To draw this parallel is not to flatten history or undermine the true suffering or the many deaths that occurred in Native boarding schools, but to unearth the ongoing influence of colonial logic in modern institutions. Please read with care.

There are profound and unsettling parallels between the structure and ideology of Native American boarding schools and contemporary eating disorder treatment centers. Native boarding schools, established throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, were state- and church-run institutions designed with a clear purpose: to assimilate Indigenous children into white settler society. These schools removed children—often forcibly—from their families and communities and placed them in distant institutions governed by white authority figures. Within these schools, Indigenous languages were banned, spiritual practices suppressed, and traditional foodways replaced with Western diets. The goal was not education but a totalizing erasure of Indigenous identity. The now-infamous phrase “Kill the Indian, save the man” encapsulated the ideological core of these institutions: cultural annihilation masked as moral and social rehabilitation.

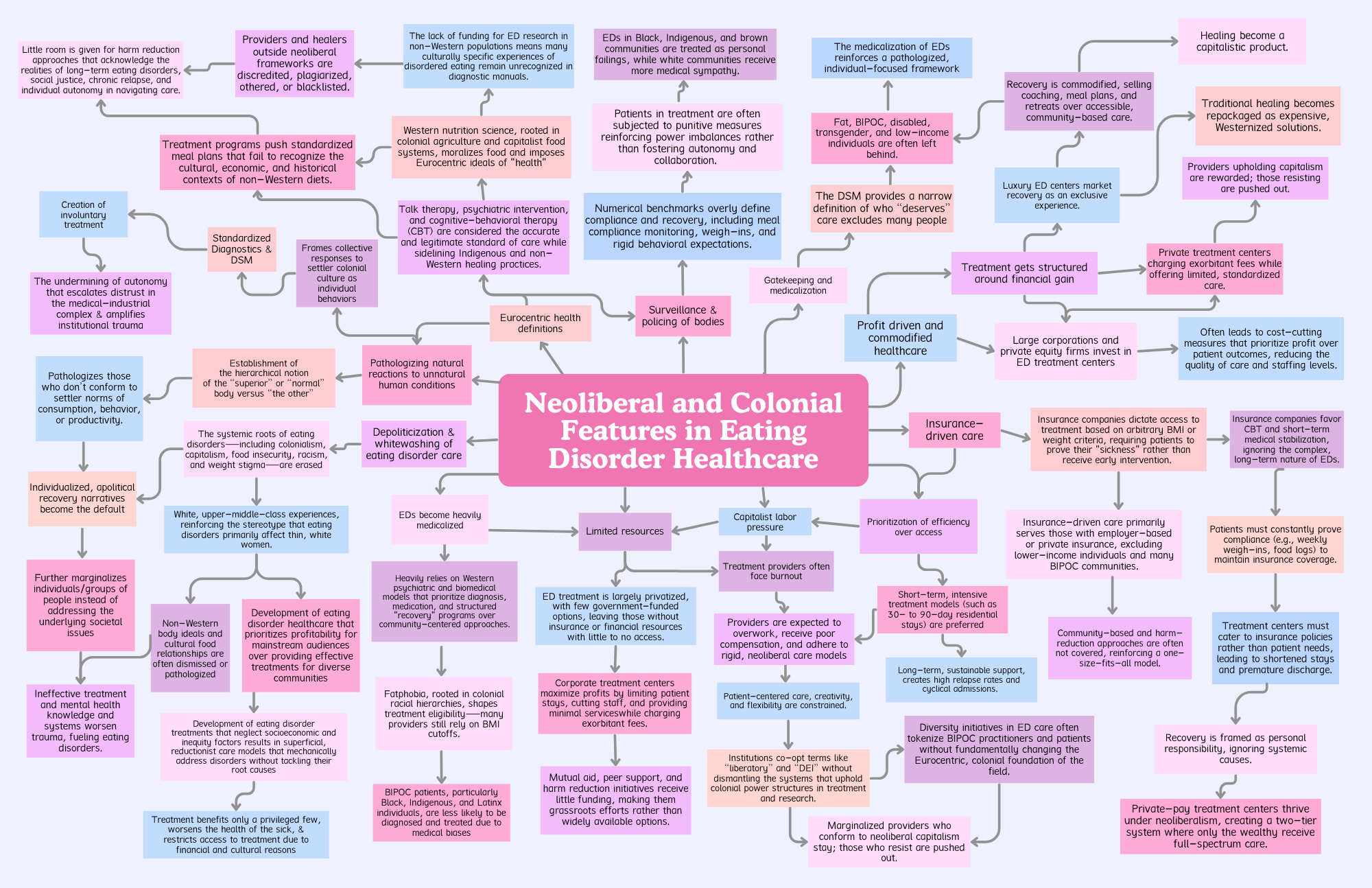

Contemporary eating disorder treatment centers, while shaped by different historical conditions, often reproduce these same logics of removal, control, and enforced assimilation. Individuals—predominantly women, queer people, people of color, and neurodivergent individuals—are often extracted from their communities and placed into residential or inpatient programs that center white, Western medical authority. In these spaces, clinicians are positioned as experts whose frameworks around food, health, and recovery are presented as universally applicable and morally superior. The body becomes a site of intervention, surveillance, and correction—detached from cultural meaning, collective experience, and personal autonomy.

To be clear: eating disorders are serious, life-threatening conditions. They carry medical implications that must not be downplayed, including organ failure, severe malnutrition, long-term disability, and death. The need for support and care is undeniable. But what also must be acknowledged is that the path to that care is too often paved with Eurocentrism, biomedical (only), erasure and coercion. A legitimate medical emergency does not justify the cultural imperialism often embedded in treatment protocols.

These institutions often function as sites of assimilation, in which clients are taught to eat, think, and behave according to dominant norms of whiteness, able-bodiedness, and middle-class respectability. The term “normal eating” is rarely examined for its racial, cultural, or political implications. Clients are not only expected to eat regularly—they are expected to eat in ways that align with Eurocentric nutrition science and white-coded ideals of discipline, portion control, and emotional regulation.

For example, the common structure of three meals and three snacks a day—often treated as the gold standard in Western nutrition and eating disorder treatment—is not a universal truth. It reflects the legacy of Western imperialism, industrial capitalism, and settler colonialism, which imposed rigid schedules onto bodies to maximize labor and erase cultural foodways.

This eating structure became normalized during the rise of factory work in 18th and 19th century Europe, where standardized mealtimes served the needs of the capitalist workday—not the needs of the body. The “lunch hour” emerged as a productivity tool, later exported globally through colonial systems like boarding schools, prisons, and hospitals.

While structured eating can support some in early recovery, enforcing it as a universal ideal disregards the rich diversity of cultural and sensory-based eating practices. For neurodivergent people, Indigenous communities, and others outside of Western norms, these rigid frameworks can feel less like care—and more like assimilation.

Much like Native boarding schools, which deemed Indigenous food systems “uncivilized” and sought to replace them with settler diets, treatment centers frequently pathologize cultural food practices and erase food traditions under the guise of clinical neutrality. But nutrition is not universal—it is culturally & spiritually constructed, economically shaped, and geographically situated. What constitutes “nourishment” in one part of the world may look radically different in another, and no singular approach can lay claim to universal truth.

In addition to cultural erasure, eating disorder treatment centers often fail to provide accommodations for neurodivergent clients. Instead of adapting care to meet the sensory, cognitive, and processing needs of autistic people, ADHDers, and others, the model typically demands that neurodivergent individuals assimilate into narrow behavioral expectations. Resistance or difficulty is often interpreted as defiance, lack of motivation, or noncompliance, rather than a signal that the treatment model itself may be inaccessible or even harmful. There is little room for harm reduction, for flexible approaches that prioritize autonomy, consent, and sustainability. Instead, treatment is often rigid, demanding total compliance in exchange for conditional care.

Surveillance is central to both Native boarding schools and eating disorder treatment centers. In boarding schools, children’s every move was monitored—language use, bodily posture, spiritual expression, and dietary access and choices were tightly controlled. In treatment, clients are monitored during meals, bathroom breaks are timed, and emotional expression is regulated. Every action becomes data for clinical interpretation. Resistance—whether it’s to a meal plan, to the rigidity of the program, or to the erasure of one’s cultural or neurodivergent identity—is pathologized. Instead of being understood as self-advocacy or self-protection, it is framed as symptomatic of illness.

Perhaps most striking is the shared belief in both systems that healing requires disconnection from community. Boarding schools removed Indigenous children from their homes in order to “save” them from their culture. Eating disorder treatment often removes individuals from their environments under the logic that proximity to community, family, or daily stressors hinders recovery. But this isolation can be profoundly harmful. It severs people from their relationships, cultural lifeways, spiritual practices, and neurodivergent routines—forms of knowledge and connection that may be essential to survival. Community is not the antithesis of care; for many, it is the only place where true healing can begin.

Both systems also reproduce a power dynamic in which white expertise is treated as objective, neutral, and morally superior, while the knowledge of marginalized people—be it cultural wisdom, lived experience, or alternative approaches to healing—is dismissed. Indigenous communities were told they had to abandon their ways of living in order to be saved. Today, eating disorder clients are often expected to abandon their culture, intuition, and autonomy in order to be “recovered.” What is framed as care is often coercion. What is called healing may actually be harm dressed in clinical language.

To draw this parallel is not to flatten history or undermine the true suffering or the many deaths that occurred in Native boarding schools, but to unearth the ongoing influence of colonial logic in modern institutions. The methods may have changed, but the ideological foundations—control, conformity, erasure—remain intact. What if, instead, eating disorder care began with the question of how to support people without asking them to become someone else? What if recovery did not require erasing identity, but instead honored complexity, cultural specificity, and neurological variation?

True healing cannot emerge from systems that demand assimilation in exchange for survival. Eating disorder care must be reimagined—grounded in autonomy, built on relationships, and flexible enough to hold the multitudes that each person brings with them. Anything less is not care—it is control masquerading as compassion.